Originally posted by: www.consumerreports.org

If you think all sunscreens touting high SPFs—like those with 50s on their labels, for example—are equally effective, here’s a surprise: Consumer Reports has found that those SPF numbers aren’t always a reliable measure of how much protection you’ll get. If you put too much faith in them, you could be putting your skin—and your child’s—at risk.

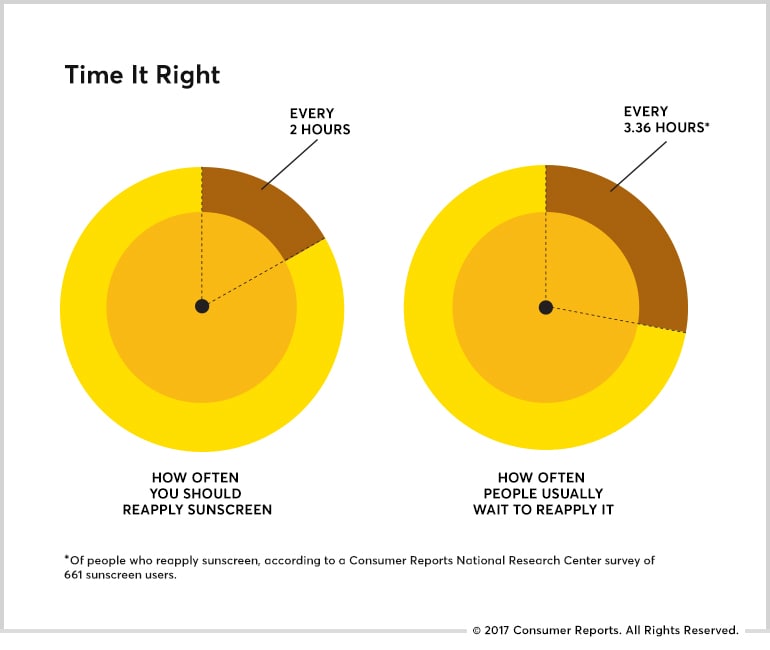

SPF, which stands for sun protection factor, is a measure of how well a sunscreen guards against ultraviolet B (UVB) rays, the chief cause of sunburn and a contributor to skin cancer. Assuming you use it correctly, if you’d burn after 10 minutes in the sun, an SPF 30 protects for about 5 hours. But the intensity of UVB rays varies throughout the day and by location, and all sunscreens must be reapplied every 2 hours you’re in the sun.

And everyone—including babies 6 months and older—needs to use sunscreen. People of color have some natural protection against UV rays. How much depends on the amount of the pigment melanin in their skin. But they are still susceptible to sunburn and skin cancer, so experts stress that sunscreen is a must for every skin tone.

For the fifth year in a row, CR’s testing has shown that some sunscreens failed to provide the level of protection promised on the package. Of the more than 60 lotions, sprays, sticks, and lip balms in our ratings this year, 23 tested at less than half their labeled SPF number.

And CR isn’t the only independent consumer organization that has found this discrepancy. Other members of International Consumer Research and Testing (a global group of consumer organizations) in Australia, New Zealand, and the U.K. have also found differences between the labeled SPF and the tested SPF in sunscreens on the market in those countries.

The ABCs of SPF

Sunscreens are classified as over-the-counter drugs. The Food and Drug Administration requires manufacturers to have their products tested to determine the SPF. But the agency doesn’t routinely test sunscreens itself. Manufacturers don’t have to report their results, although they do have to submit them to the FDA if the agency requests them.

At a public meeting last June, an FDA official said the agency had the resources for only about 30 employees to cover more than 100,000 over-the-counter drugs. That limits what it can do to oversee sunscreens.

“Most of the time, a sunscreen’s effectiveness has been verified only by the manufacturer and any testing lab it might decide to use—and not by the government,” says William Wallace, an analyst for Consumers Union, the policy and mobilization arm of Consumer Reports.